![]()

The United States is a nation divided: that is one of the most dominant narratives that emerged during this year’s presidential race.

That reality—missed by pollsters, pundits and political experts alike—helped to explain the popularity and stunning electoral victory of Republican Donald Trump over Democrat Hillary Clinton.

The other story of 2016 is the rise of so-called “fake news” and its spike on social media outlets. Facebook, in particular, has come under fire, having surpassed Google as the biggest driver of audience on all social media platforms.

This week, Trump again invited controversy — a move now commonly called a “tweet storm” — by tweeting out a claim of voter fraud during the November election that he says denied him the popular vote without citing any evidence.

The “fake news” phenomenon has rattled the web, not to mention mainstream journalists, scholars and ordinary users of social media, many of whom are tweeting and writing op-ed columns, news stories and guides on how to spot inaccurate news stories and fake news websites.

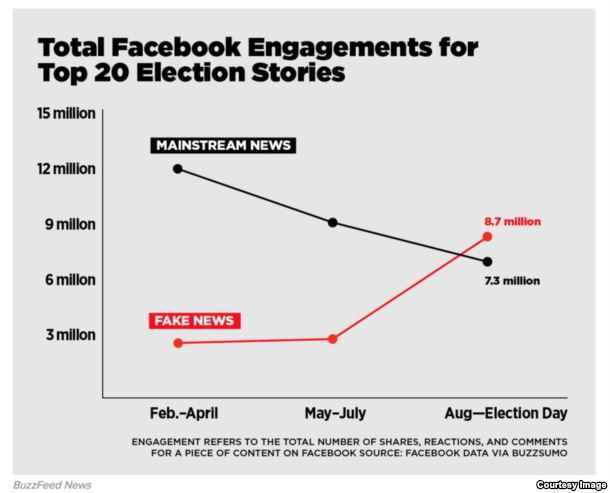

All this has put unprecedented pressure on Facebook, where, according to an analysis by Buzzfeed News, fake election stories generated more total engagement on Facebook than top election articles from 19 major news outlets in the final three months of the election campaign.

The heat on Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg prompted the company to tweak its algorithm to weed out inaccurate information, and later, as the outcry grew, publicly outline steps the company is taking to reduce what Zuckerberg called “misinformation.”

He prefaced his post with a familiar caveat:

“We do not want to be arbiters of truth ourselves, but instead rely on our community and trusted third parties.”

There are legitimate sites, journalists and scholars who are paying attention to the prevalence of “fake news.” Among them: Snopes.com, Columbia Journalism Review, The Poynter Institute and Melissa Zimdars, an assistant professor of communication and media at Merrimack University, who wrote a Google document with tips on how to spot “fake news” sites or inaccurate news stories for her students.

According to these fact-checkers, we must first understand what “fake news” is – and isn’t.

“We classify ‘fake news’ as specifically web sites that publish information that’s entirely fabricated,” said Kim LaCapria, content manager for Snopes.com, a website that tracks misinformation on the web.

“Right now ‘fake news’ is being applied to ‘slanted and/or inaccurate news,’” added LaCapria. “So there’s some conflation.”

And that conflation of what information can accurately be described as fake or misleading or maybe only partially true, coupled with the warp speed of digital platforms like Facebook and Twitter, have created a perfect storm of confusion, said University of Connecticut philosophy professor and author Michael Lynch.

“Confusion and deception is happening…. and mass confusion about the importance of things like truth follow in the wake of that deception,” said Lynch, who wrote a column in The New York Times this week about impact of “fake news” on the health of America’s political system. “And that is absolutely corrosive to democracy.”

LaCapria, like Lynch, also has seen first-hand how branding everything that is verifiably false “fake news” isn’t really what is happening on social media. “One long-circulating rumor held that Hillary Clinton was fired from the Watergate investigation for lying,” LaCapria said.

“If I recall correctly, we rated it mostly false because the claim originated with someone who had changed his story over the years. But in our politics category, the news is not fake per se. It’s often false, mixture, mostly false or unproven.”

LaCapria points out distorted or false information has existed for a long time.

“This is the first real social media election we’ve ever experienced. And we had two social media candidates: [Bernie] Sanders and Trump,” she said.

“Now that people are upset about Trump, they’re looking at social media as a culprit. And it may be a mitigating factor, but this has all definitely been affecting politics hugely for many years.”

The Poynter Institute’s Alexios Mantzarlis, who leads the International Fact-Checking Network, agrees that there is a bit too much angst over “fake news.”

“Politicians distorting the truth isn’t a new phenomenon. Voters choosing politicians based on emotions rather than facts is not a new phenomenon,” Mantzarlis said in an email. “Moreover, we know from research that fact-checking can change readers’ minds.”

For social media companies like Twitter and the rest, the ability to weed out false information or hate speech can be daunting, no matter how savvy their back-end web engineers may be.

Facebook in essence acknowledged that recoding its algorithm wasn’t enough, when Zuckerberg posted his latest statement about the spreading of misinformation on his platform.

For Lynch, who wrote “The Internet of Us: Knowing More and Understanding Less in the Age of Big Data,” a book released earlier this year, there are solutions to help combat the ease of creating “fake news” sites and spreading misinformation across the web.

“There are a lot of smart people working on social media and at universities trying to find algorithmic solutions to misleading content and confusion and deception on the Internet. Right now it’s not working,” he said. But right now I don’t think we should despair about not fixing our technology.”

In terms of fixes, Mantzarlis puts the burden on users.

“For one, headline writers could avoid repeating a baseless claim without any indication that it is unfounded.” Mantzarlis also argues that Facebook will need to hire some human beings to vet content in tandem with creating smarter back-end technology.

“The algorithm itself will have to change … to recognize that ‘fake news,’ and the pages that consistently post them, to get a reduced reach on [the Facebook] News Feed,” he said, adding that this tack will hit “fake news” purveyors where it hurts the most.

“After all, for many the incentive to publish this content is financial and if the reach is reduced, so is their income.”

Most agree that the overwhelming noise of the Internet — and the much-heralded freedom of speech ethos that rules it — will forever include distortions of fact and outright falsehoods. But ultimately the vast majority of web content is created by people. And in Lynch’s mind, that is where the real power to spot and call out misleading information lies.

“I’ve become convinced that as I’ve gone around talking to people, including those in Silicon Valley … is that we as individuals, as people, need to start taking responsibility for what we believe. And for what we share and tweet.”

—————————————————————————

From : Voice of America / November 29, 2016

Link : http://www.voanews.com/a/fake-news-spurs-angst-in-the-internet-age/3616571.html